GUIDE TO DROWNING MERCH: How I Saved the Museum Souvenir Business

Luxury Merch Confessions: The Billion-Dollar Secret Museums Don't Want You to Know

Picture this: the last days of March 2021. America is slowly emerging from the pandemic. Cultural hunger is intensifying, and immersive shows are becoming a lifeline for the industry.

My friends launched a project of immersive shows across twenty venues throughout America, but soon after the exhibitions opened, it became clear—the merchandise was a complete disaster.

As the store director said: "Our souvenir shop is a graveyard of Chinese knockoffs. And thousands of people pass through it daily, having just experienced the powerful impact of Van Gogh's art."

From Disappointment to Inspiration

I began work on my first premium merchandise collection on the night of March 28th. Symbolically, this was the day when Van Gogh painted his first picture in Arles. The day before he sent his letter to Theo about his "Sunflowers."

And it came to pass! My collection didn't just save the exhibition; it sparked a revolution in the world of artistic merchandise.

Birth of a Concept

When Giuseppe Cipriani invented his famous Bellini cocktail at Harry's Bar in Venice, he followed a simple idea: create something that would match the place, atmosphere, and clientele of the establishment. Peach juice and prosecco—a perfect balance.

I followed the same principle when developing the collection for Van Gogh. I needed a perfect balance between recognition and originality, accessibility and premium quality, commercial potential and artistic value.

The main mistake of the previous merchandise was the straightforward reproduction of paintings on objects. Van Gogh on a mug, Van Gogh on a t-shirt, Van Gogh on an umbrella... As if the great artist was just a supplier of pictures!

I decided to take a different path—to create items that would embody the essence of Van Gogh's work, his color combinations and graphics, rather than simply using his images.

https://open.spotify.com/episode/3BDDozjjoPwZdaye0vAmEt?si=PgNE8tKcRE6BiAwAOy_zUQ

From Disappointment to Inspiration

I began work on my first premium merchandise collection on the night of March 28th. Symbolically, this was the day when Van Gogh painted his first picture in Arles. The day before he sent his letter to Theo about his "Sunflowers."

And it came to pass! My collection didn't just save the exhibition; it sparked a revolution in the world of artistic merchandise.

Birth of a Concept

When Giuseppe Cipriani invented his famous Bellini cocktail at Harry's Bar in Venice, he followed a simple idea: create something that would match the place, atmosphere, and clientele of the establishment. Peach juice and prosecco—a perfect balance.

I followed the same principle when developing the collection for Van Gogh. I needed a perfect balance between recognition and originality, accessibility and premium quality, commercial potential and artistic value.

The main mistake of the previous merchandise was the straightforward reproduction of paintings on objects. Van Gogh on a mug, Van Gogh on a t-shirt, Van Gogh on an umbrella... As if the great artist was just a supplier of pictures!

I decided to take a different path—to create items that would embody the essence of Van Gogh's work, his color combinations and graphics, rather than simply using his images.

https://open.spotify.com/episode/3BDDozjjoPwZdaye0vAmEt?si=PgNE8tKcRE6BiAwAOy_zUQ

Three Key Principles of Collectible Merchandise

After a sleepless night reading Van Gogh's letters to his brother Theo, I formulated three principles that became the foundation not only for the first collection but for all my subsequent work:

First—emotional authenticity. Each item should evoke the same emotions as the artist's works. For Van Gogh, this meant the intensity of the blue color, the sense of movement, the emotional fullness.

We created silk scarves where the brushstrokes of "Starry Night" were drawn in 3D volume with a relief brush. This created a tactile sensation of depth—like on a real painting. And the skulls of the smoking skeleton from his painting transformed into a stylish print on black cashmere scarves.

Second—artistic interpretation instead of copying. Rather than simply transferring a painting onto an object, we interpreted it through the prism of functionality.

For example, we didn't print "Sunflowers" on notebook covers. Instead, we created an abstract texture of brushstrokes whose color palette and rhythm referenced the painting. Only true connoisseurs understood the reference.

Champagne flutes were adorned with elegant irises with gold framing, packaged in tubes. After unpacking, these tubes began living their own lives—people would store pencils or pens in them. The objects inhabited home interiors, extending the exhibition experience.

And third—material quality as respect for the artist. We decided that every material in the collection should be of such quality that Van Gogh himself would approve.

For notebooks—only paper from sustainable sources with high density. For textiles—natural fabrics: silk, cotton, wool. For accessories—genuine leather and quality metal, without cheap alloys.

After a sleepless night reading Van Gogh's letters to his brother Theo, I formulated three principles that became the foundation not only for the first collection but for all my subsequent work:

First—emotional authenticity. Each item should evoke the same emotions as the artist's works. For Van Gogh, this meant the intensity of the blue color, the sense of movement, the emotional fullness.

We created silk scarves where the brushstrokes of "Starry Night" were drawn in 3D volume with a relief brush. This created a tactile sensation of depth—like on a real painting. And the skulls of the smoking skeleton from his painting transformed into a stylish print on black cashmere scarves.

Second—artistic interpretation instead of copying. Rather than simply transferring a painting onto an object, we interpreted it through the prism of functionality.

For example, we didn't print "Sunflowers" on notebook covers. Instead, we created an abstract texture of brushstrokes whose color palette and rhythm referenced the painting. Only true connoisseurs understood the reference.

Champagne flutes were adorned with elegant irises with gold framing, packaged in tubes. After unpacking, these tubes began living their own lives—people would store pencils or pens in them. The objects inhabited home interiors, extending the exhibition experience.

And third—material quality as respect for the artist. We decided that every material in the collection should be of such quality that Van Gogh himself would approve.

For notebooks—only paper from sustainable sources with high density. For textiles—natural fabrics: silk, cotton, wool. For accessories—genuine leather and quality metal, without cheap alloys.

Chinese Factory: Battle for Quality

When I showed the first sketches to a friend, he asked: "Where are you going to produce all this magnificence?" "In China," I replied. "But that's where all this junk came from!" he exclaimed, gesturing toward the rejected merchandise. "The problem isn't China. The problem is who sets the task and how," I explained.

Chinese factories aren't a monolithic mass of junk producers. They're a complex ecosystem where alongside cottage workshops exist enterprises that produce for Prada and Louis Vuitton.

I spent many years in China, practically living in factories. I know so much about Chinese production that sometimes I wish I could be wrong, but as always, I know exactly what will happen.

I rejected the first five batches of silk because the shade of blue wasn't "Van Gogh enough." I made them redo the hardware for notebooks because the click when closing wasn't deep enough.

Local technologists initially thought I was crazy. But when they learned that I was willing to pay for quality and wasn't chasing speed, their attitude toward my orders changed.

When I showed the first sketches to a friend, he asked: "Where are you going to produce all this magnificence?" "In China," I replied. "But that's where all this junk came from!" he exclaimed, gesturing toward the rejected merchandise. "The problem isn't China. The problem is who sets the task and how," I explained.

Chinese factories aren't a monolithic mass of junk producers. They're a complex ecosystem where alongside cottage workshops exist enterprises that produce for Prada and Louis Vuitton.

I spent many years in China, practically living in factories. I know so much about Chinese production that sometimes I wish I could be wrong, but as always, I know exactly what will happen.

I rejected the first five batches of silk because the shade of blue wasn't "Van Gogh enough." I made them redo the hardware for notebooks because the click when closing wasn't deep enough.

Local technologists initially thought I was crazy. But when they learned that I was willing to pay for quality and wasn't chasing speed, their attitude toward my orders changed.

Moment of Truth: The First Collection

Samples of our collection arrived in Chicago—just in time for the exhibition opening. The foundation consisted of:

Cashmere scarves "Starry Night" and "Smoking Skull" with elaborate prints. Each scarf was packaged in a box with volumetric prints like sunflower petals and yellow silk ribbons.

Ceramic candle holders "Bedroom in Arles"—miniature versions of furniture from the famous painting. When a candle burned, shadows on the walls of the holder moved, creating an effect similar to Van Gogh's brushstrokes.

A set of 6 wine glasses and 6 champagne flutes with images of starry night, irises, sunflowers, and skulls. Each was packaged in a tube box with ornaments of sunflowers and irises.

I stood at the entrance to the souvenir shop on opening day, observing the reaction of the first visitors. When an elderly lady opened a box with a scarf and involuntarily gasped, I knew: we were on the right track.

By the end of the first weekend, the shop had exceeded its monthly sales plan. And after two weeks, my phone was ringing off the hook with calls from other cities where the exhibition was held. Everyone wanted the same merchandise.

Samples of our collection arrived in Chicago—just in time for the exhibition opening. The foundation consisted of:

Cashmere scarves "Starry Night" and "Smoking Skull" with elaborate prints. Each scarf was packaged in a box with volumetric prints like sunflower petals and yellow silk ribbons.

Ceramic candle holders "Bedroom in Arles"—miniature versions of furniture from the famous painting. When a candle burned, shadows on the walls of the holder moved, creating an effect similar to Van Gogh's brushstrokes.

A set of 6 wine glasses and 6 champagne flutes with images of starry night, irises, sunflowers, and skulls. Each was packaged in a tube box with ornaments of sunflowers and irises.

I stood at the entrance to the souvenir shop on opening day, observing the reaction of the first visitors. When an elderly lady opened a box with a scarf and involuntarily gasped, I knew: we were on the right track.

By the end of the first weekend, the shop had exceeded its monthly sales plan. And after two weeks, my phone was ringing off the hook with calls from other cities where the exhibition was held. Everyone wanted the same merchandise.

From Van Gogh to Monet: Birth of the "Constellation of Impressionists"

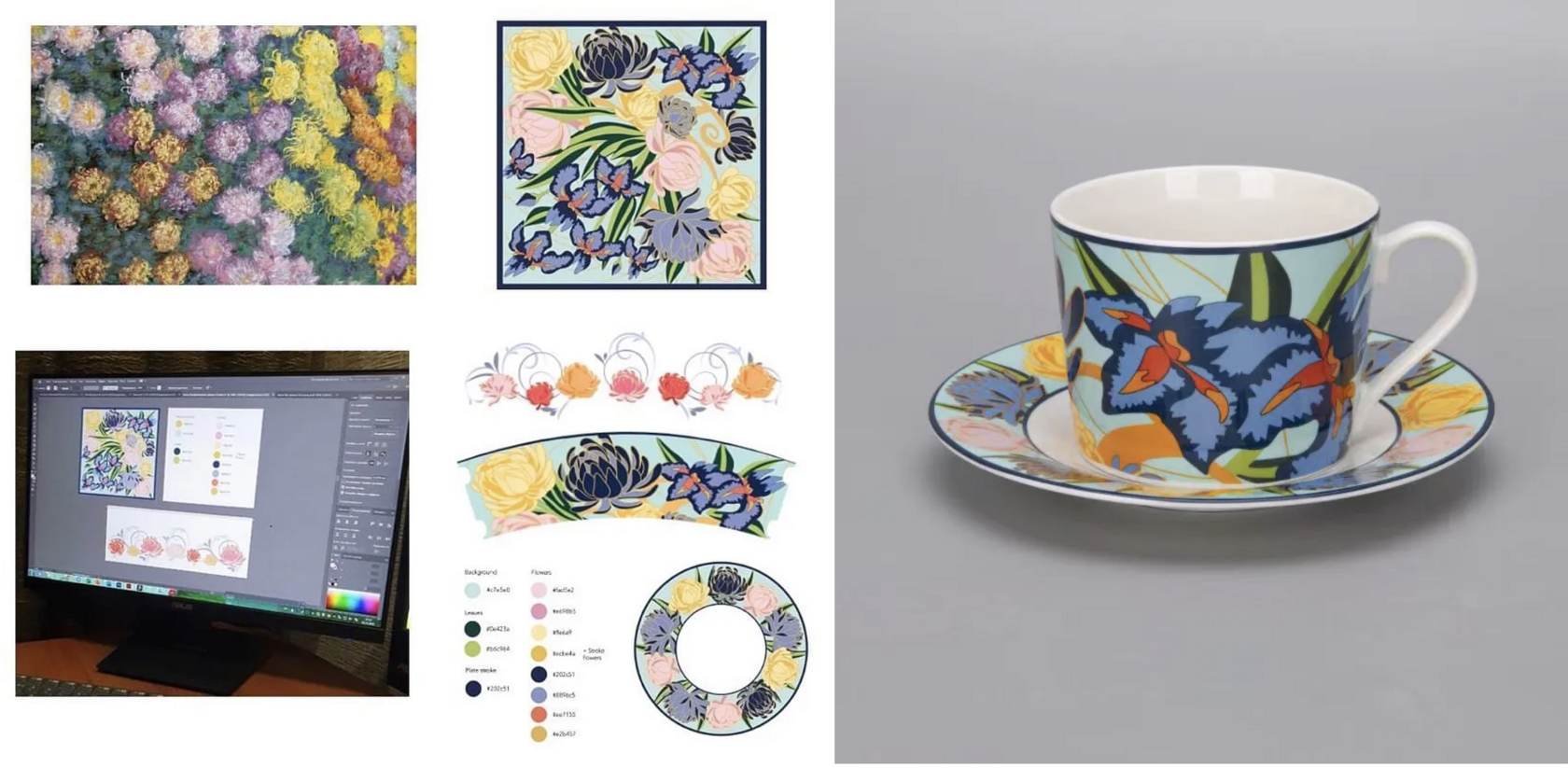

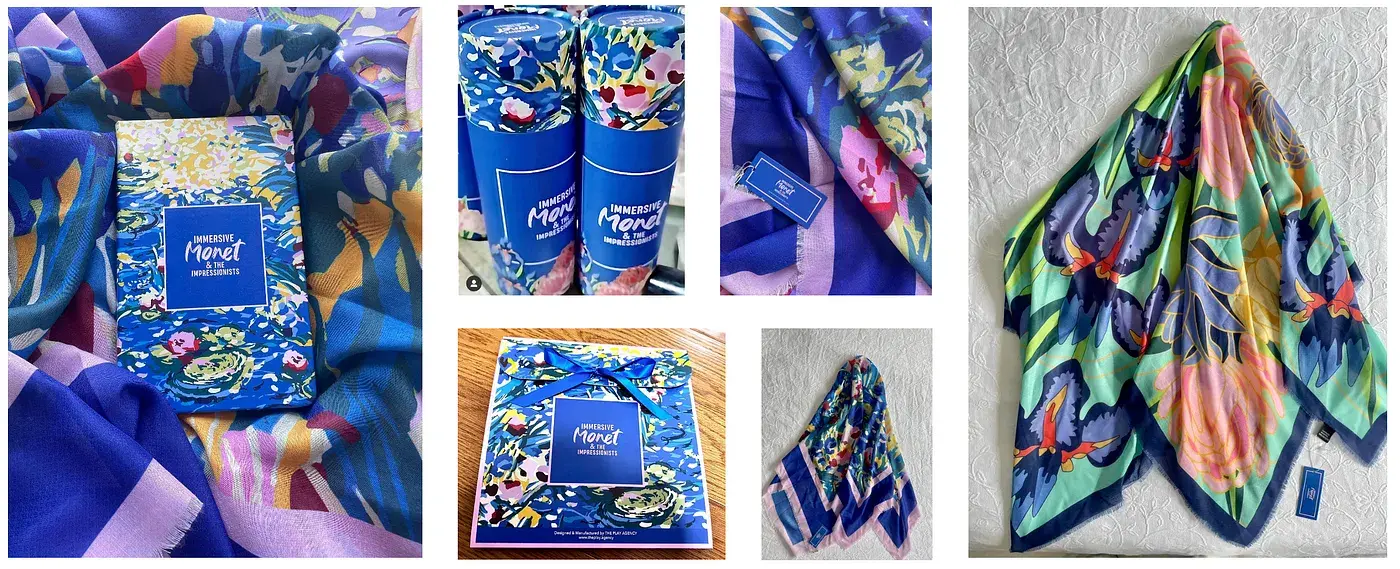

The success was so overwhelming that we were asked to create collections for other immersive exhibitions. The next was Claude Monet's exhibition.

This is when the concept of the "Constellation of Impressionists" was born—a series of interconnected collections where each artist is represented by their unique style, but all are united by a common aesthetic and can be collected as a whole.

For Monet, we created the "Water Gardens" collection—a series of items related to reflections and water. Particularly popular were glasses and flutes painted with water lilies and chrysanthemums. There were cashmere and silk scarves with our original flower prints, tea sets with cups and saucers in gift boxes, plates and mugs made of Chinese porcelain.

Each item had its unique number and QR code that led to a page with the creation story and connection to the artist's work. This transformed merchandise from a simple souvenir into an educational tool.

The success was so overwhelming that we were asked to create collections for other immersive exhibitions. The next was Claude Monet's exhibition.

This is when the concept of the "Constellation of Impressionists" was born—a series of interconnected collections where each artist is represented by their unique style, but all are united by a common aesthetic and can be collected as a whole.

For Monet, we created the "Water Gardens" collection—a series of items related to reflections and water. Particularly popular were glasses and flutes painted with water lilies and chrysanthemums. There were cashmere and silk scarves with our original flower prints, tea sets with cups and saucers in gift boxes, plates and mugs made of Chinese porcelain.

Each item had its unique number and QR code that led to a page with the creation story and connection to the artist's work. This transformed merchandise from a simple souvenir into an educational tool.

Secret of Success

What was the secret to the success of our collections? Why did people who used to walk past souvenir shops now stand in lines and pay $180 for a silk scarf?

I identify five key factors:

First—emotional connection. We weren't selling products with pictures. We were selling a way to extend the emotional state that the visitor experienced at the exhibition. Our items became a bridge between the elevated experience of art and everyday life.

Second—a story told. Each item had its own story related to the life and work of the artist. This story was conveyed through design, materials, packaging, and accompanying materials.

Third—collectible value. We deliberately created connections between different items and collections, transforming the purchase from a one-time act into a long-term passion. Some visitors specifically traveled to exhibitions in other cities to add to their collection.

Fourth—quality without compromise. We never economized on materials and execution. Even the simplest mug in our collection was produced with such attention to detail that it became an object of admiration and a traditional part of a tea set.

And fifth—balance of exclusivity and accessibility. Each collection had items of different price categories: from porcelain mugs for $15 to silk scarves for $180. But even the most affordable items carried the same philosophy of quality and attention to detail.

What was the secret to the success of our collections? Why did people who used to walk past souvenir shops now stand in lines and pay $180 for a silk scarf?

I identify five key factors:

First—emotional connection. We weren't selling products with pictures. We were selling a way to extend the emotional state that the visitor experienced at the exhibition. Our items became a bridge between the elevated experience of art and everyday life.

Second—a story told. Each item had its own story related to the life and work of the artist. This story was conveyed through design, materials, packaging, and accompanying materials.

Third—collectible value. We deliberately created connections between different items and collections, transforming the purchase from a one-time act into a long-term passion. Some visitors specifically traveled to exhibitions in other cities to add to their collection.

Fourth—quality without compromise. We never economized on materials and execution. Even the simplest mug in our collection was produced with such attention to detail that it became an object of admiration and a traditional part of a tea set.

And fifth—balance of exclusivity and accessibility. Each collection had items of different price categories: from porcelain mugs for $15 to silk scarves for $180. But even the most affordable items carried the same philosophy of quality and attention to detail.

Conclusion: From San Michele to Eternal Life

The island of San Michele in my beloved Venice is the final resting place of many great creators. But their works continue to live, inspire, and influence new generations.

Similarly, truly great merchandise collections don't die after an exhibition closes. They continue to live as cultural artifacts, as evidence of a certain epoch and aesthetic.

Now, years after the first Van Gogh collection, some items from it are sold at auctions for prices five to six times higher than the original cost. They have become collectibles, small works of art.

And this is perhaps the main lesson I've learned from my experience: true premium merchandise is a continuation of art in a new form. It's a way to make great art part of everyday life, to bridge the gap between the museum experience and home space.

As Joseph Brodsky might say, paraphrasing his famous quote: "In my next life, I would like to be born as an object of true art, even if it's a Van Gogh silk scarf."

The island of San Michele in my beloved Venice is the final resting place of many great creators. But their works continue to live, inspire, and influence new generations.

Similarly, truly great merchandise collections don't die after an exhibition closes. They continue to live as cultural artifacts, as evidence of a certain epoch and aesthetic.

Now, years after the first Van Gogh collection, some items from it are sold at auctions for prices five to six times higher than the original cost. They have become collectibles, small works of art.

And this is perhaps the main lesson I've learned from my experience: true premium merchandise is a continuation of art in a new form. It's a way to make great art part of everyday life, to bridge the gap between the museum experience and home space.

As Joseph Brodsky might say, paraphrasing his famous quote: "In my next life, I would like to be born as an object of true art, even if it's a Van Gogh silk scarf."

museum merchandise, van gogh merch, souvenir shop makeover, artistic merchandise, immersive exhibitions, art business success, collectible souvenirs, museum shop transformation, premium merchandising, emotional branding